Veterinary Expert: Ticks, Fleas Not Just a Seasonal Problem

Warmer weather is upon us and pet owners tend to think about tick and flea control for their dogs and cats. But according to a veterinary parasitology expert at Auburn University’s College of Veterinary Medicine, this should not be just a seasonal concern.

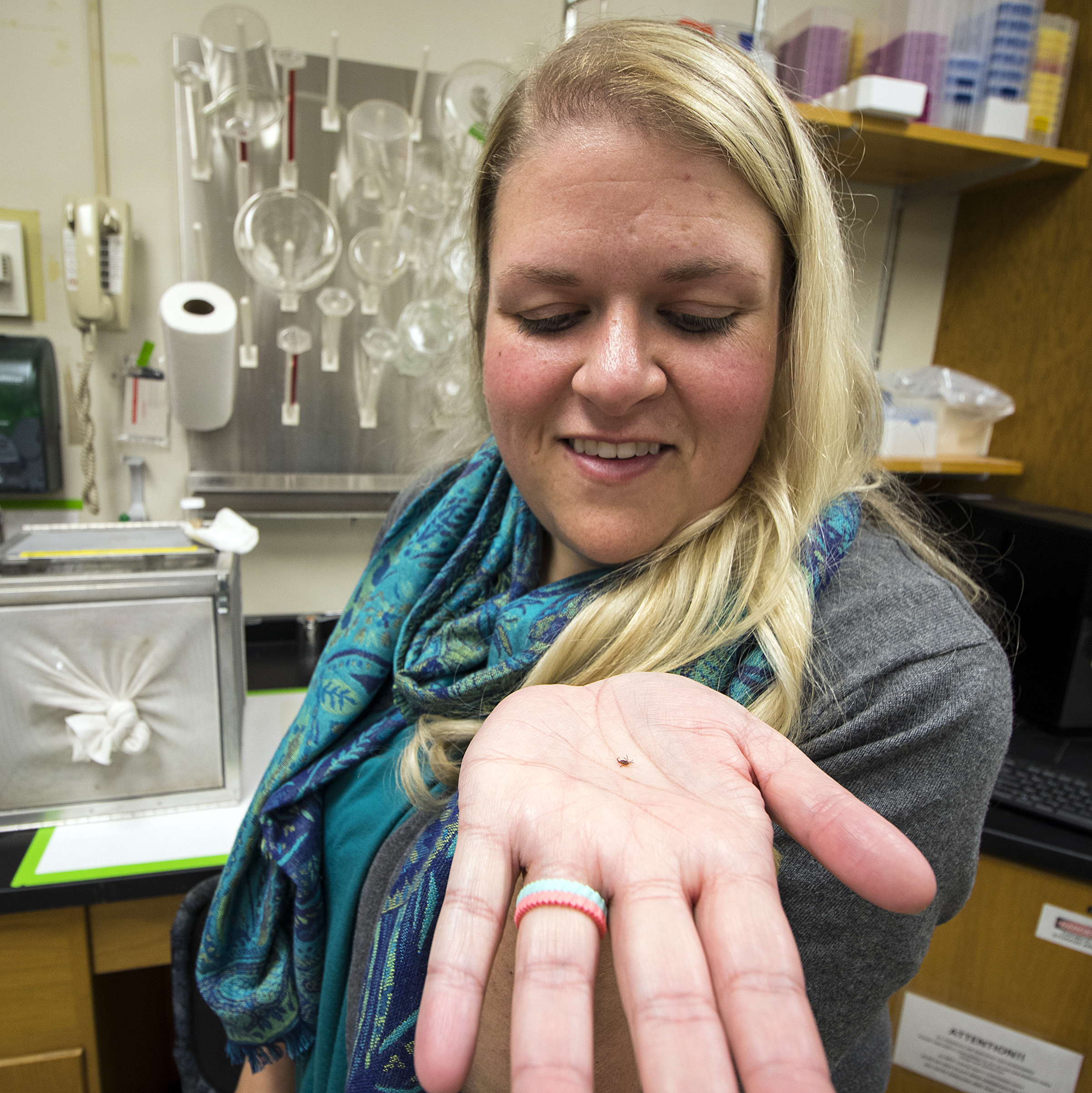

“A tick problem is not just a summer problem,” said Dr. Lindsay Starkey, an assistant professor in the Department of Pathobiology whose veterinary medicine subspecialty is parasitology. “That is a common misconception. Fleas and ticks can survive in winter and some even indoors. Ticks can survive a cold, damp winter better than they can a hot, dry summer. Pet and other animal owners need to protect their animals year round.”

Dr. Starkey teaches a range of parasitology courses to first-, second- and fourth-year veterinary students. She also assists with the parasitology component of veterinary student’s diagnostics rotation that is part of their four-year clinical year of veterinary education.

“Parasitology is hugely important to veterinarians and for veterinary students to learn,” Dr. Starkey said. “Unfortunately, even with the good medications that we have, parasites are going to walk into the door of a veterinarian’s practice every day. And when it is fleas and ticks—these parasites can carry a number of potential pathogens, such as the bacteria that cause Rocky Mountain spotted fever, Lyme disease, ehrlichiosis and plague.”

Parasite problems are particularly prevalent in the South, Dr. Starkey says, and it’s not only ticks and fleas that are vectors, but also mosquitoes. “Heartworm is incredibly common in the Southern states, but is found throughout the U.S. Dogs, and also cats and a few other animals, are infected through the bite of a mosquito,” she said.

Veterinary researchers continually work toward the development of better drugs for parasite control, and, currently, there are very good medications available for use in pets. However, Dr. Starkey says that the need for precautions extends even to large animals and humans. She offers some suggestions for year-round precautions for parasite control for pets and their owners:

For Pets:

- Year-round prevention using a veterinarian-recommended medication designed for treating and controlling fleas, ticks, heartworm and other parasites;

- Check the pet routinely for evidence of a flea or tick infestation;

- Treat the areas indoors and outside where the pet lives and plays;

- Manage the outdoor environment to make it less conducive for harboring ticks, fleas and mosquitoes;

- Remove standing water which serves as a breeding ground for mosquitoes;

- “Tick-scaping,” which involves such techniques as chemical treatment, mowing and minimizing leafy areas that can harbor ticks and fleas in the yard.

For Humans:

- Use a good insect repellant such as DEET or permethrin;

- Wear long sleeves and long pants to protect against ticks and mosquitoes;

- Tuck pant legs into the tops of shoes and boots;

- Tuck in shirt tails;

- And always self-check the body for ticks after being in a potential tick environment.

“Sometimes ticks are so small that it is nearly impossible to find them on your body,” Dr. Starkey said. “But when one has attached itself, there are safe ways to remove them. Use forceps or fine tweezers and grab the tick as close to the attached area on the skin as you can. Gently, but steadily pull the tick away from the skin to remove it and don’t twist or bend. Squeezing the tick may actually cause the tick to inject more toxins or pathogens back into the bite area.”

The same removal techniques apply to removing ticks from a pet, Dr. Starkey adds.

Symptoms that a pet owner should be watchful for that might indicate the animal has a parasite-borne illness includes fever, loss of appetite or limping.

“Concerned animal owners can save the removed tick in a plastic bag or other container and bring it into their veterinarian to have it identified or sent out for pathogen testing,” Dr. Starkey said. “And, always check thoroughly. If you find one tick, there very well might be more.”

-30-

(Written by Mitch Emmons, emmonmb@auburn.edu)